|

| Fig. 38: A richly decorated stucco interior of a house on the Stokstraat in 1934 |

From 1815 onwards – when Maastricht became part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands – Maastricht grew into its position as the first industrial city in the Netherlands, following the example of the Walloon city of Liège, in modern-day Belgium. The small crafts production from the medieval city was converted into industry in the northern part of Maastricht, where a transshipment port (het Bassin, 1824-1825) and a canal connection with the northern part of the Netherlands (Zuid-Willemsvaart, 1822-1826) had already been built. In 1834, Petrus Regout started his first pottery factory there and the rest is history. Between 1830 and 1839, a few more attempts at secession raged in the southern Netherlands, resulting in Belgium and Maastricht being definitively assigned to the Netherlands. Around 1835, therefore, a (considerable) part of the elite and the intelligentsia left the city in protest. It was not until the late twentieth century that Maastricht made the transition from a manufacturing and industrial city to a knowledge and services city. Only then did Maastricht's current rich, touristic and international image come about.

|

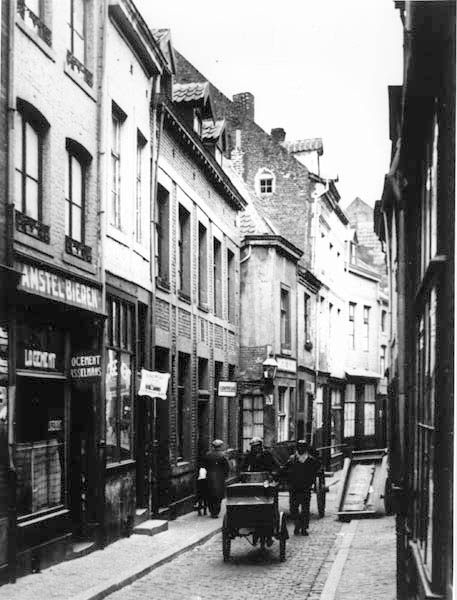

| Fig. 39: Busy merchandise and inhabitants in the Stokstraat |

Although the Stokstraat is now one of the most expensive shopping streets in the Netherlands, this was quite different a few decades ago. The street was once comprised with large and luxurious houses for the early industrialists. But when the fortress status of Maastricht expired in 1867, these residents were the first to move to cleaner, more spacious residential areas just south of Maastricht, to the so-called Villapark.

|

| Fig. 40: Empty houses in 1959 in the Stokstraat, ready to be torn down |

These old houses on the Stokstraat were increasingly inhabited by more and more people, who earned their small amounts of money as industry workers. Close to the factories of the Sphinx Porcelain Company, such people were housed in ‘warehouses’ in the Boschstraatkwartier, but also in this southern part of the old city, the Stokstraatkwartier. Most rooms were occupied by an entire family. The backyards and courts were overbuilt, until it was a neighborhood in which poor families lived in ever degrading conditions. After a research-project, the city council said it wanted to solve this problem and did this by labeling the people as anti-socials (crapuul) and by re-educating them in so-called residential schools. Maastricht had five residential schools, of which the Ravelijn is the best known.

Reference:

F. Bokern, Crapuul. Kroniek mvan een krottenwijk, Amsterdam, 2022.