As the Pokémon franchise evolved, it amassed a large number of fans and maintained its popularity over many years (Laato & Rauti, 2021), the official Pokémon YouTube channel, for example, has 5.73 million subscribers as of March 2024. Despite the significant cultural differences between the East and the West, Pokémon still appeals to global fans due to the popularisation of Japanese popular culture. Recently, scholars Laato and Rauti (2021) have dived deeper into Pokémon’s fandom and examined the narrative style and storytelling ways of Pokémon.

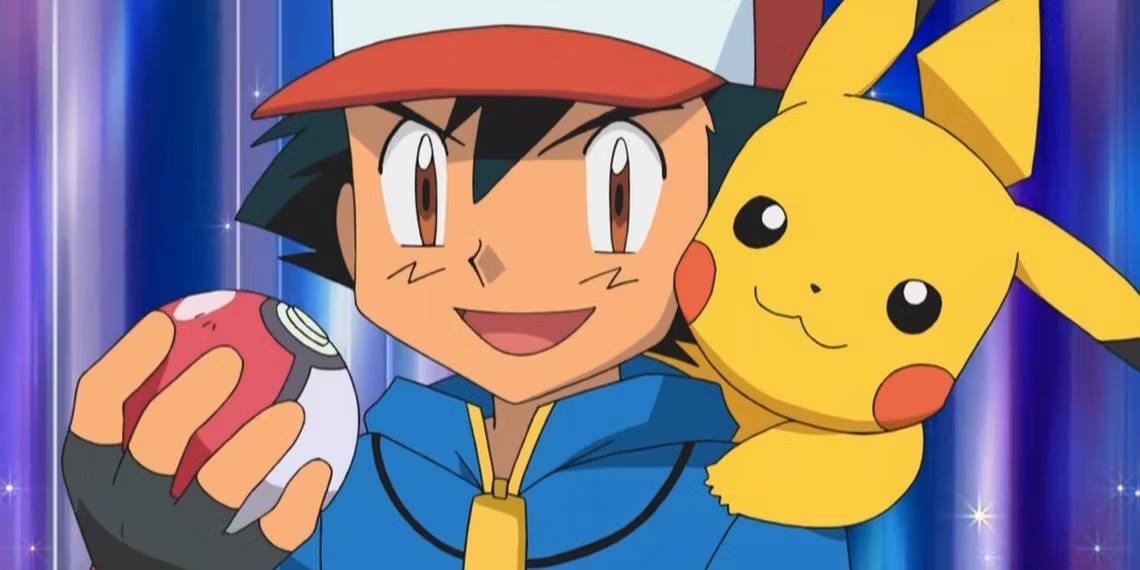

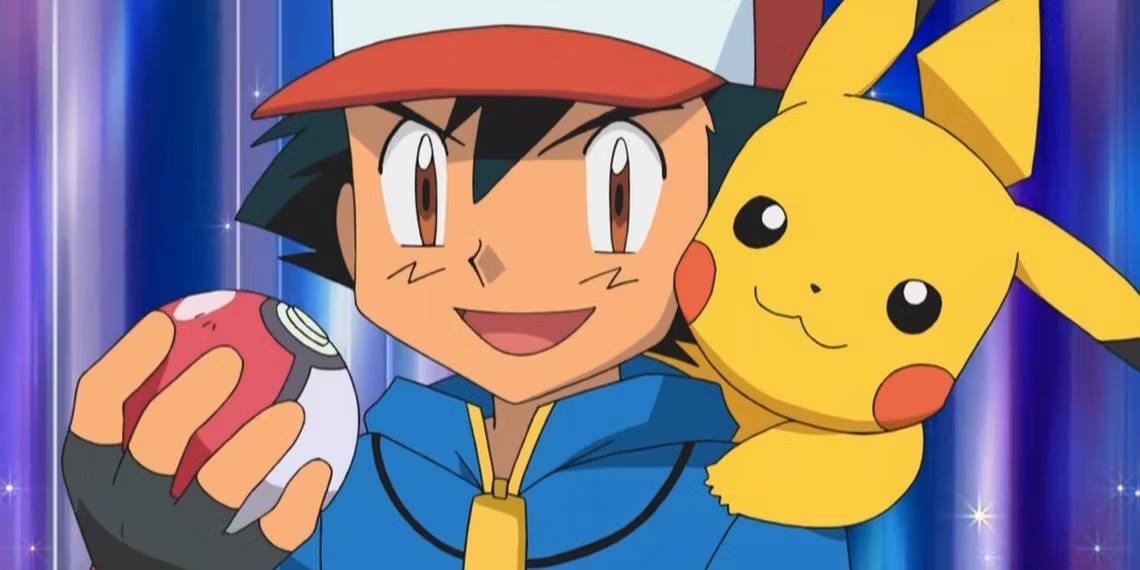

There are four major themes presented in the games and the TV series that make this franchise so appealing to such a large audience, the first being “the relationship between a trainer and their Pokémon” (Laato & Rauti, 2021). The Pokémon franchise emphasizes the partnership, respect and mutual growth between the humans and their Pokémon. Laato and Rauti (2021) argue that the portrayed ability of these “monsters” as being capable of forming deep bonds and experiencing emotions with humans is appealing to the audience’s sensibilities.

The second theme is “the interaction with nature” (Laato & Rauti, 2021), as players are encouraged to venture into various environments and explore the cultural diversity of the Pokémon game worlds. The Pokémon franchise utilized technology to enhance the user experience and add depth and meaning to the exploration to ultimately make the Pokémon world a space as much for adventuring and imagination as for learning.

Thirdly, the society as portrayed in the games and TV series functions “in the form of inter-human relationships, trading, barter and social belonging” (Laato & Rauti, 2021), which offers players and viewers an allegory on social integration, conflict resolution and the significance of connection and teamwork.

Lastly, Laato and Rauti (2021) also note the appeal of “futuristic technology and living in symbiosis with the environment”. This is portrayed in the games and TV series through the application of green and advanced technology, almost exclusively powered by highly specialised Pokémon, who simply use their innate abilities to perform a task. For example, electric type Pokémon—meaning: their powers are based on electricity—provide power to the grid, while mounts, i.e. Pokémon that can be mounted like horses, are the default method of transportation in this universe, negating the need for cars or other carbon-emitting technology (Zelvin, 2019).

Bainbridge, J. (2013). “It is a Pokémon world”: The Pokémon franchise and the environment. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 17(4), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877913501240

Gervasoni, Q. (2021). Is Pokémon for children? How fan participation and transmedia practices transform age boundaries of audiences. In V. I. de La Ville, G. Brougère, & P. Garnier (Eds.), Cultural and Creative Industries of Childhood and Youth. An interdisciplinary exploration of new frontiers. Peter Lang Verlag. https://doi.org/10.3726/b17816

Laato, S., & Rauti, S. (2021). Central Themes of the Pokémon Franchise and why they Appeal to Humans. In B. Tung X (Ed.), Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 2814–2823). https://doi.org/10.24251/hicss.2021.344

The Official Pokémon YouTube channel. (2005). Youtube.com. http://www.youtube.com/@pokemon

Zelvin, V. (2019, July 31). Pokémon is a Solarpunk Utopia. Medium; SUPERJUMP. https://medium.com/super-jump/pok%C3%A9mon-is-a-solarpunk-utopia-9f8791873d4

MickTK. (2023). Walking through nature helps discovering new Pokémon [Online GIF]. In GitHub. https://github.com/MickTK/PE-Pokemon-Color-Variants

TV Tokyo. (2014). Ash and Pikachu [Online image]. In The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/08/pop-writing-8-24-14/378840/